Back in September I wrote the Exchange Monitoring Concerns? Pick Up the Slack article for TechGenix (later posted in my blog as Exchange alerting using Slack) about monitoring Exchange and sending mobile alerts to administrators using Slack, a messaging app for teams. At the time, Slack was one of the best apps I could find to easily generate alerts on mobile devices.

A few weeks ago, Microsoft announced Microsoft Teams, a competitor to Slack. From my short experience with it, Microsoft Teams seems to work great, especially since it’s fully integrated with the rest of the Office 365 suite. To learn more about Microsoft Teams, please watch this Microsoft Mechanics video.

The question now is: can we use Microsoft Teams to alert administrators on their mobile devices when something is wrong with their systems or application (such as Exchange)? Let’s find out!

Signing Up to Microsoft Teams

At the time of writing this article, Microsoft Teams is available in preview (since November 2, 2016) to eligible Office 365 commercial customers (Business Essentials, Business Premium, and Enterprise E1, E3, E4 and E5). It is expected the service will become generally available in the first quarter of calendar year 2017.

To turn on Microsoft Teams, IT admins should go to their Office 365 admin center, click Settings, click Organization profile and scroll down to Release preferences. In here, ensure preview features are enabled:

Now click on Apps:

On the list of available apps, search for Microsoft Teams and enable the service, plus all the required features you want to use:

Accessing Microsoft Teams

For some reason, after enabling Microsoft Teams, its icon is still not available in the app launcher:

However, if we navigate to https://teams.microsoft.com we will be able to login to the service just fine.

Similar to Slack, and many other Office 365 applications, Microsoft Team is available in three versions: web app, desktop app, and mobile app.

The purpose of this blog post is not to explain how to use Microsoft Teams (the Microsoft Mechanics video is a great place to start on that), but to see if and how we can use the service to programmatically send alerts to administrators on their mobile devices. But before we do so, we need to use the web or desktop apps to do some initial configuration. So let’s get to it.

Setting Up Microsoft Teams

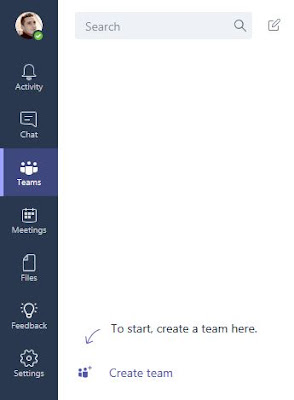

The first step to configuring Microsoft Teams is to login to https://teams.microsoft.com, select Teams and create our first team by clicking on Create team:

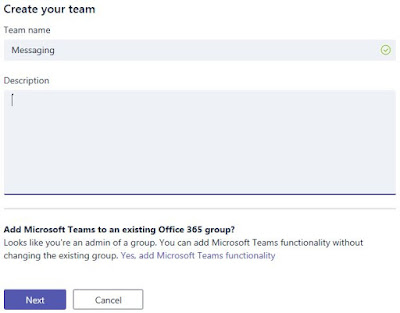

Next we give our new team a name and a description (optional). If we are currently the owner of an Office 365 Group, we get the option to add Teams functionality to that group:

The final step (optional) is to add one or more members to our new team:

If we add users, each will receive an email notifying them they have been added to our new Messaging Team:

We now have our first Team created :)

Each Team can have multiple channels. Channels are how Microsoft Teams organizes conversations. We can set up our channels however we like: by topic, discipline, project, and so on. Channels are open to everyone on the team and contain their own files, OneNote, etc...

So let’s create one channel just for alerts by clicking on ... next to our team’s name and then Add channel:

Give the channel a name and click Add:

We now have our Alerts channel dedicated to Exchange alerts:

Configuring WebHook Connector

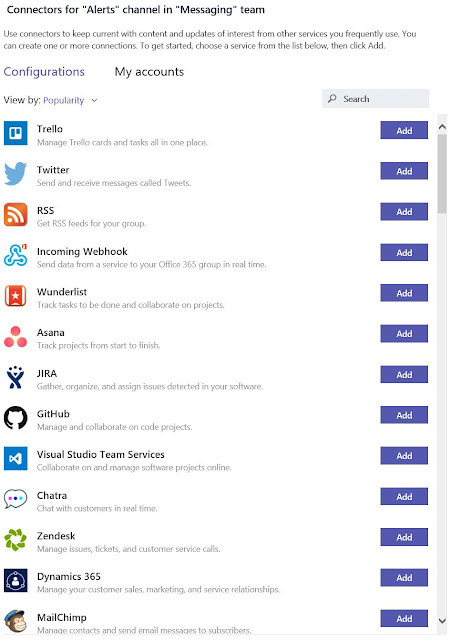

Office 365 Connectors are used to get information and content into Microsoft Teams. Any user can connect their team to services like Trello, GitHub, Bing News, Twitter, etc., and get notified of the team's activity in that service. Connectors also provide a way for developers to integrate with Microsoft Teams by building custom incoming WebHook Connectors to generate rich cards within channels.

To generate our alerts to administrators, we will create these cards (messages) by sending an HTTP request with a simple JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) payload to a Microsoft Teams webhook address.

First, we need to create a webhook address for our Alerts channel:

1. From within Microsoft Teams, click ... next to the channel name and then select Connectors:

2. Scroll through the list of connectors to Incoming Webhook, and click Add:

3. Enter a name for the webhook, upload an image to associate with data from the webhook (optional), and select Create:

4. Copy the webhook URL to the clipboard and save it. We will need this URL for sending information to our channel:

5. Click Done and a message will be visible in the Conversations tab informing all members that an incoming webhook has been configured for the channel:

We now have our webhook configured which we will use to post messages to our Alert channel. If we go into Connectors one more time, we are informed that an Incoming Webhook is already configured and by whom. If we click on Manage we get the options to change its name (which I have changed to AlertsBot) and to remove the webhook.

Please be aware that any member of the team can get the webhook URL and use it to send messages. On top of that, any member can also remove the webhook...

Sending Messages to Microsoft Teams

Now that we have our webhook configured, we need a method to send an HTTP request with a JSON payload to the webhook address. To achieve this, we have two options. The first option is to use cURL, a tool used in command lines or scripts to transfer data with URLs. Since my workstation is 64-bit, I downloaded the Win64 - Generic version (at the time of writing this blog, v7.51.0).

From the command line (not PowerShell), we can use the following command to send a basic “Hello World!” message to our channel:

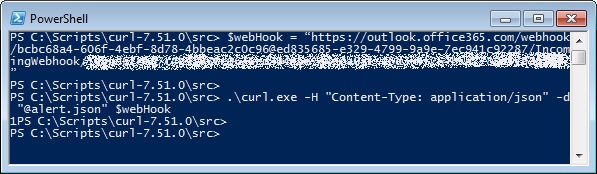

curl.exe -H “Content-Type: application/json” -d “{\”text\”: \”Hello World!\”}”Doing the same using PowerShell and cURL is a bit more tricky because of the “ (quotes) within the code. In the example above we used \” to escape the quotes, which will not work with PowerShell. The easiest method I found was to put the whole payload in a file (let’s call it alert.json, but we can also use alert.txt for example) and then pass the file into cURL. The file will look like this:

$webHook = “https://outlook.office365.com/webhook/bcbc68a4-606f-4ebf-8d78-4bbeac2c0c96@ed835685-e329-4799-9a9e-7ec941c92287/IncomingWebhook/(...)"

.\curl.exe -H “Content-Type: application/json” -d “@alert.json” $webHook

• Invoke-RestMethod: sends HTTP/HTTPS requests to Representational State Transfer (REST) web services;

• ConvertTo-Json: converts any object to a string in JSON format. The properties are converted to field names, the field values are converted to property values, and the methods are removed.

Using these two cmdlets, we don’t need cURL anymore. Our previous “Hello World!” example becomes simply the following:

$webHook = “https://outlook.office365.com/webhook/bcbc68a4-606f-4ebf-8d78-4bbeac2c0c96@ed835685-e329-4799-9a9e-7ec941c92287/IncomingWebhook/(...)”

$alert = ConvertTo-JSON @{

text = “Hello World!”

}

Invoke-RestMethod -ContentType “application/json” -Method Post -body $alert -Uri $webHookIf we manually run the code just to see what the variable $alert contains, we will see that it is in the exact same (JSON) format as our alert.json file:

$webHook = “https://outlook.office365.com/webhook/bcbc68a4-606f-4ebf-8d78-4bbeac2c0c96@ed835685-e329-4799-9a9e-7ec941c92287/IncomingWebhook/(...)”

$exchDB = Get-MailboxDatabase “MDB01” -Status | Select Name, LastFullBackup, DatabaseSize, Mounted, ServerName

$userCount = (Get-Mailbox -Database $exchDB.Name -ResultSize Unlimited).Count

$size = $($exchDB.DatabaseSize.Split(“(“)[0])

$alert = ConvertTo-Json -Depth 4 @{

text = “**$($exchDB.Name) Information:**”

sections = @(

@{

facts = @(

@{

name = "Database:"

value = $exchDB.Name

},

@{

name = "Last Bck:"

value = $exchDB.LastFullBackup

},

@{

name = "Size (GB):"

value = $size

},

@{

name = "Mounted?"

value = $($exchDB.Mounted)

},

@{

name = "On Server:"

value = $exchDB.ServerName

},

@{

name = "User Count:"

value = $userCount

}

)

}

)

}

Invoke-RestMethod -ContentType "application/json" -Method Post -body $alert -Uri $webHook

$webHook = “https://outlook.office365.com/webhook/bcbc68a4-606f-4ebf-8d78-4bbeac2c0c96@ed835685-e329-4799-9a9e-7ec941c92287/IncomingWebhook/(...)”

While ($True) {

[Int] $msgCount = 0

Get-TransportService | Get-Queue | Where {$_.MessageCount -gt 0 -and $_.DeliveryType -notlike "Shadow*"} | ForEach {$msgCount += $_.MessageCount}

If ($msgCount -gt 50) {

$alert = ConvertTo-Json -Depth 1 @{

text = “**High Mail Queues!**`nTotal queued emails: $msgCount”

}

Invoke-RestMethod -ContentType "application/json" -Method Post -body $alert -Uri $webHook

}

Start-Sleep –Seconds 1800

}The purpose of this post was not to test Microsoft Teams itself, but to test if it can be used to reliably alert administrators on their mobile devices with any potential issues with Exchange.

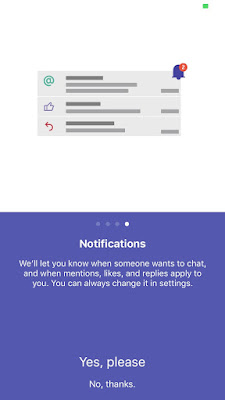

We already established that we can easily generate alerts to a Teams’ channel, but what we now need to test is Microsoft Teams’ mobile app. To show how platform-independent Microsoft Teams is, I am going to use an iPhone to test the mobile app (trust me, I am not an Apple fan) :)

We start by searching and downloading the app from the Apple Store:

At this stage it seems that I only get an alert on my mobile phone when someone mentions me:

The problem is that I haven’t been able to find a way of mentioning someone or a channel using cURL or PowerShell... :( This means that users will get the messages on their mobile devices but not a notification, making this method not suitable for what I am trying to achieve... This, of course, until I find a way of mentioning someone using JSON!

I found an article on Bot Builder for .NET that has a section about Activities and Mention Entities. This article states that we can mention someone using a JSON like this:

{

...

"entities": [{

"type":"mention",

"mentioned": {

"id": "UV341235", "name":"Color Bot"

},

"text": "@ColorBot"

}]

...

}So using both the web and desktop Team apps, I sent a few messages where I mentioned someone and captured the JSON payload to see exactly how these are constructed and sent. For example, the following message:

Conclusion

Surely I am missing something here because of my lack of JSON knowledge and experience... As such, it might be that adding or changing something really simple will make it work! As is, I can’t yet use Teams to reliably alert me until I figure how to mention someone...

Nonetheless, Microsoft Teams is an awesome product and I am looking forward to explore it even further!